Utilizing a Strength-based Approach to Teaching Students with Disabilities in Staten Island Schools

A Staten Island special education teacher describes how she utilizes a strength-based approach to teach students with disabilities.

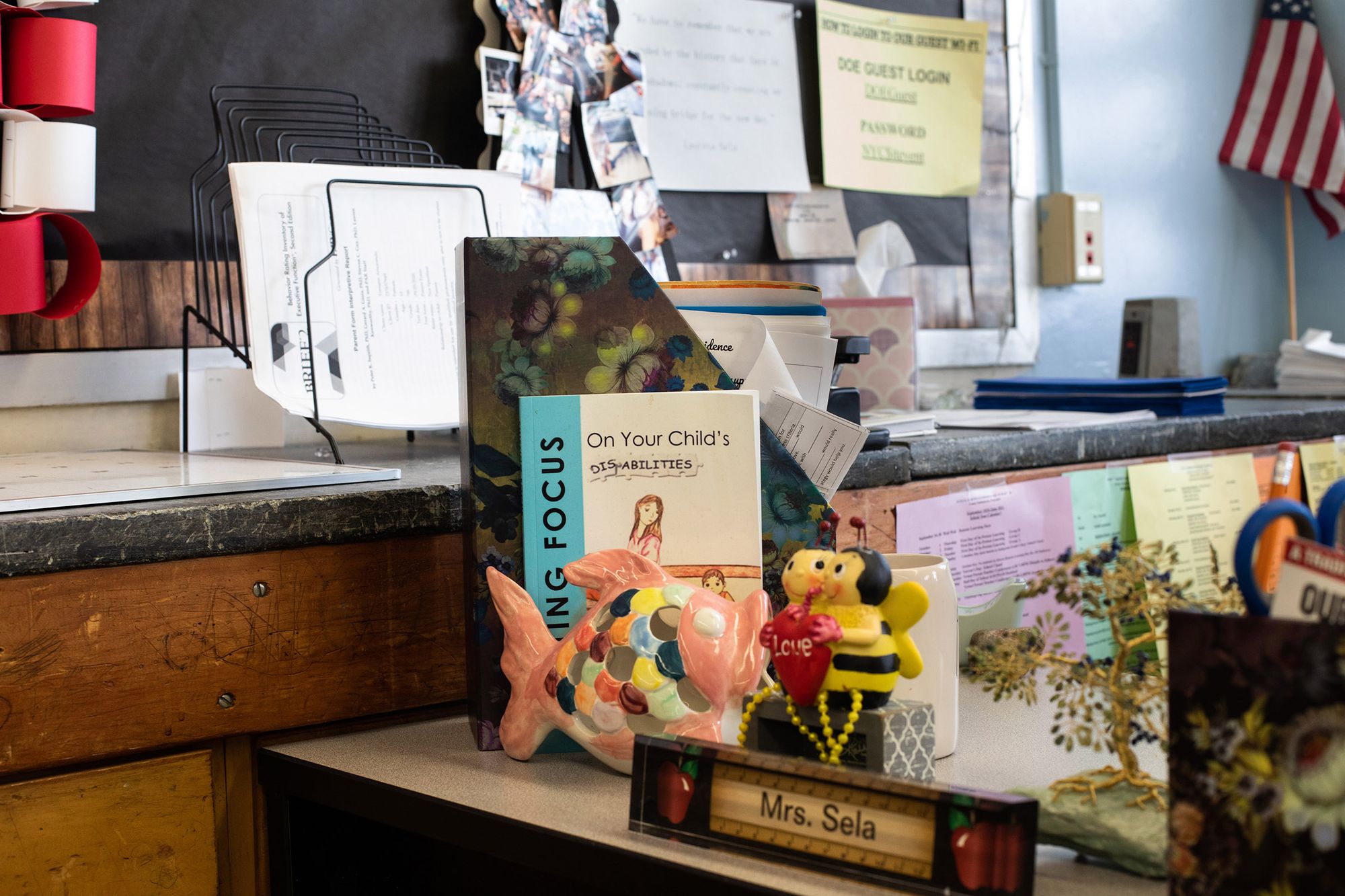

Shifting Focus by Staten Islander, Amy Sela, is an accessible guide for parents and teachers on how to implement a strength-based approach for children with disabilities. The short book is filled with practical exercises and lessons drawn from Sela’s eleven-year career as a special education teacher and paraprofessional as well as from her experiences as a mother of four. She advocates that special education professionals shift from primarily a deficit-oriented mindset to focusing more attention on identifying and cultivating a child's strengths and interests. Research reviews on a strength-based approach to teaching have shown how the method can improve academic outcomes, builds student confidence, and results in a more hopeful student outlook.

In an interview, Plea for the Fifth asks Sela more about the strength-based approach in her book, how she’s adapted that approach to remote learning, and her vision for improved school instruction for students with disabilities.

Students with Disabilities on Staten Island

Approximately 15,000 students, or about one in four students, in Staten Island’s School District 31 have disabilities, including intellectual disabilities, emotional disturbances, and physical impairments. According to the latest DOE data, only 50 percent of those students fully received the services they are entitled to during the current school year, a significant drop from previous years. This drop is attributed mainly to barriers caused by remote learning. City officials have commented that the actual conditions may be better than the reported data because of potential gaps in this year’s data entry. Last summer a number of rallies took place on Staten Island to advocate for increasing in-person special education services during the pandemic. At the end of January, a civil rights class action lawsuit filed by three Staten Island children and their mothers argued that the 2,000 students with disabilities in District 75 schools on the Island face segregation and other discriminatory practices. District 75 schools are located in each borough and serve only students with disabilities. In the current Community Education Council (CEC) elections, improving the quality of special education is a major issue on many of the platforms of Staten Island candidates. In order to increase equity, this is the first year that any NYC public school parent can vote in CEC elections up until May 11.

*Plea for the Fifth’s interview with Amy Sela was edited for length and clarity.

Plea for the Fifth: How has being a paraprofessional helped you understand your students better as a special education teacher?

Amy Sela: When I was first hired to become a para, I knew that I was going to help a student with a disability. But it wasn't until after a couple of weeks later that I realized all the strengths and abilities that that student was holding. I don't think I would have figured that out as a teacher. Teachers usually have 8 to 12 students if it's in a self-contained class. But in the Integrated Co-Teaching (ICT) class, we have 33 or 35 kids. You're not going to be able to get to know that child with a disability as well. But they're bright kids in their own way. I remember being able to highlight them, throughout those classes— the strengths they were good at, so that they felt that confidence. They're already being seen as they can't do it. But if you start highlighting their strengths, it gives them motivation that they need, so that when they do go to that class that they are not that good at, they have that ability to try.

Plea For the Fifth: How do you use the strength-based approach you encourage in your book with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs)?

Amy Sela: The way that our IEPs are written are basically deficit-based. A child can’t do this, a child has trouble doing that, this child is not up to the seventh grade standards. I've been starting to initiate professional developments to teach teachers how to write strength-based IEPs by using the child's strengths as leverage to help them with their weaknesses.

It could be anything—say that child works well on their own. Sometimes we as teachers are forced to group students or forced to make them work independently. Sometimes a child with disabilities can't do those things. Why are we forcing them to? We could set those abilities in the IEP instead of just talking about the standards that they can’t reach. Instead we can ask, “How can they reach those standards?” These are little things that you can use to help the child build that motivation inside them, build that fuel, that fire, to help them become successful every day.

Plea for the Fifth: Can you talk about how common core standards can actually be used as a tool to differentiate and support students with disabilities?

Amy Sela: We all follow standards everyday through our daily lessons. I used to have these on my desk every day [holding up common core standards]. And then the students would be familiarizing themselves with that standard. And they could see what level of work they could do every single day. At the end of the lesson, they would then self-assess themselves. It's used as what we would call a set of success criteria. They will look at their work and see which standard they hit. If they were at a level one, they would try to see how they could get to a level two and then two to three. But maybe it was a question that they were especially interested in that day, and they will probably get a three and then can move on to a four. So every day you would kind of get something different, but then it will kind of average out to a standard that they were close to reaching for that year or for that unit.

So not only are you supporting your students that are struggling, you also allow your higher level students to advance to a higher level. You're supporting both— you're supporting the general population as well as your special ed. population or just anyone who's falling behind.

Example Success Criteria:

Plea For the Fifth: In schools, a big part of learning is the social and emotional aspect; it’s really important for creating a positive and inclusive learning environment. How do you support students with disabilities with socializing, so they’re not isolated from general education students?

Amy Sela: I started a club called Social Corner for my school because I noticed how my self-contained students had a difficult time adjusting in the lunchroom. They would come back to class stressed and frustrated from the noise and behaviours. So I had my self-contained students play board games with the general ed population in the lunchroom. It was a simple idea. I didn't realize what it was going to become. I started noticing my special ed students mingling with my gen ed students, having conversations laughing, and having a good time. They began to socialize and pick up social cues and behaviors that they normally were not used to. During the lunch period it became so successful that other teachers opened up their doors to have their kids come in their rooms to play board games too. You'd be surprised with kids these days, they're very empathetic, which is a nice thing to see. If a student is struggling or having a bad time, which I noticed when they were playing board games, they were supporting those students.

I think that we shouldn't really have self-contained classes. I feel like students with disabilities should be placed in the general population with support from the special ed teachers. We've come so far that we have all these service providers, but I feel like the placement in a self-contained environment that we put our kids in right now is not giving them that opportunity to grow socially. Why can't they learn together with a special ed teacher on the side there in the classroom like an ICT setting?

Plea for the Fifth: During the pandemic, there's been a lot of challenges to remote learning and not having the students in the physical space with you. How have you been able to use technology with one of the tips that you give in the book—figuring out students’ interests and then connecting them to the lesson plan? Universal Design for Learning shows how methods like this benefit not only students with disabilities but all students.

Amy Sela: It's a simple survey in the beginning of the year that you can give out to your students, just to try to figure out what their interests are and incorporate them in your daily lessons as much as you can. Interesting thing is, every time I do this, I notice that there's so many commonalities. Kids usually like the same types of things. They're growing up together, watching the same shows, playing the same games. There is going to be a couple of places where you can find a common ground. And you can incorporate that in your lessons. One example is that the kids are so into the game Among Us. They were playing it like crazy. We started incorporating the game into our lessons. I teach history, so we would use it when it came to figuring out who the Paleo Indians [the Lithic Peoples] were, learning different tribes. Or it could be a silly meme that you put up, and then we'll all laugh for five minutes. But it has to be related to the content. Things like that show that you care about them. It works well for students with disabilities, but it's also working for all the students.

Plea for the Fifth: In your book you discuss how assistive technology can be the future for schools. Even though the pandemic has been really challenging, what are some opportunities that you've had to explore how technology can help with individualized instruction and self-directed learning?

Amy Sela: With this pandemic, every kid was getting an iPad, and schools were getting all of these devices too. Whereas in the past, we never had that. Maybe the computer class had technology, but not every department had computers or laptops in the classrooms. This year, students got to learn about technology. Now that we have it available and students have the skills, I feel like it would be an amazing time to purchase assistive technology programs that enable every student to learn at their own pace. Students would get their individual lessons based off of where they're at. And then they could move themselves up to the next levels on their own.

Plea for the Fifth: How do you create more positive student teacher dynamics?

Amy Sela: I just think that we [educators] need to change our mindset. Support could be used in other ways to help students become more social, more independent, and more advanced in the areas where they could achieve. You can have students involved as young as second grade and ask them what works best for you? You have the student take ownership. And then when that student goes on to the next grade and meets a new teacher, they can say, “Well, this is something that works best for me. This is how I learned best.”

PIea for the Fifth: I think that’s really changing the narrative because I feel sometimes when people talk about students with disabilities, they think of them as powerless, and they always need to be advocated for. But what you're really talking about is how these students can speak up for themselves. They have strengths, they are good at things. We just need to support them, and they will let us know what to do.

Amy Sela: There hasn't been a student that I worked with that wasn't capable of doing that, however “low functioning” someone may say that they were. Students have the capability to self-advocate. We just got to give them the power to do so, and switch that power over to them. As teachers, we understand supports, we understand differentiation, and scaffolding. But what if we don't understand the kid? Let the kids tell us what they need, they're the expert on themselves.

I think that the narrative needs to change in a big way. And it won't just help students with disabilities, it'll help all students because we have so many students falling through the cracks. Not only for students with disabilities but also for students of color and ESL students. How are we going to close the achievement gap for all students? Let's use this new narrative for them. Let's make kids know that we believe that they can do it. Let them show us how.

Cover photograph: Author and educator Amy Sela photographed in her classroom at I.S. 24 in Great Kills, Staten Island on May 6, 2021. Photograph by Olga Ginzburg for Plea for the Fifth

Disclaimer: Plea for the Fifth reporter, Valeriana Dema, and interviewee, Amy Sela, are distant extended family members. The main goal of this article is to share how a strength-based approach can be used as a tool to teach students with disabilities. However, it's also a top priority for Plea for the Fifth to be as transparent as possible about any conflicts of interest.